Blockchain Voter Apathy

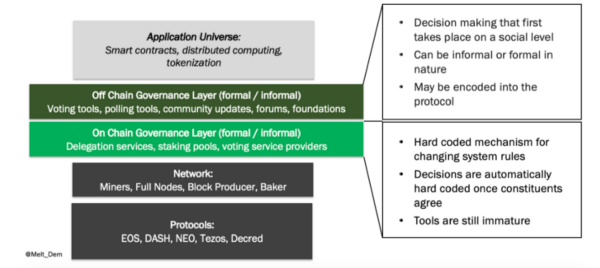

Governance is a key area of exploration for blockchains today. There are typically two layers of governance: off-chain and on-chain. Much has already been written on the trade-offs between on-chain and off-chain governance. This post will not explore the merits of either position, but rather the barriers and potential solutions to increased voter participation generally.

Blockchains require some form of governance to help the community make adjustments or improvements to the network, like changing certain core parameters like the Block Size or adding new capabilities like SegWit which enable scalability improvements like the Lightning Network.

Notable examples of off-chain governance include Bitcoin Improvement Proposals (BIP) and Ethereum Improvement Proposals (EIP), which are designed to introduce new features to Bitcoin and Ethereum, respectively.

The typical cadence of off-chain governance is as follows. First, a stakeholder (developer, economic actor, etc.) conducts research and develops a formal proposal. Proposal discussion then occurs across social mediums like #CryptoTwitter, online forums (ETHResear.ch, Reddit), Core Developer meetings, and/or mailing lists. The community, including Core Developers, will review the proposals, provide feedback and decide whether to accept the proposal off-chain. Generally, a significant majority is required to adopt a proposal. Once a proposal is pushed through and widely communicated, node operators will then need to upgrade their software. Proposals are typically batched together for release in a future fork (i.e the Constantinople hard fork included 5 EIPs).

In contrast, on-chain governance activity occurs “on the blockchain”. The major implementations of on-chain governance today feature on-chain voting like Decred’sPoliteia, which allows stakeholders to vote on funding for Decred’s treasury, or Tezos’ multi-step amendment process, in which Tezos token holders can vote on protocol-level changes, such as increasing gas limits as proposed in the recent Athens proposal (more on that later).

While unproven, with many prominent critics noting that on-chain voting can lead to plutocracies and oligopolies, the broader trend of on-chain governance is an important narrative to watch as blockchains continue to evolve.

For those interested in reading more about governance, I highly recommend Fred Ehrsam’s “Blockchain Governance: Programming our Future”.

Decentralized Voter Turnout

As on-chain governance continues to evolve, there has been momentum with several on-chain votes recently taking place. While the scope of proposals have varying degrees of importance, voter turnout might be extrapolated as a *very general* indicator of community participation within decentralized governance.

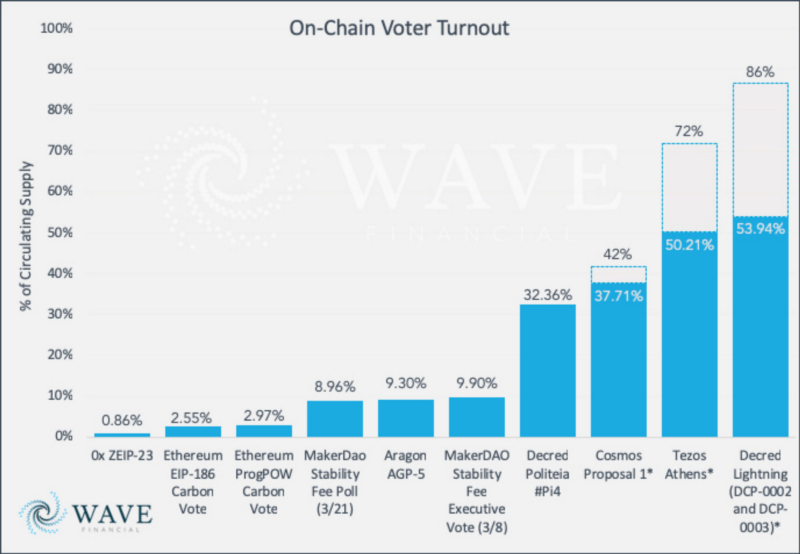

The chart below outlines voter turnout represented as a % of circulating token supply for a number of recent proposals. As a rough reference point to the real world, Brexit voter turnout was 72.2%, the average voter turnout for US presidential elections is 50–55% and average U.S. corporate voter turnout historically hovers around 75%.

These data points are by no means comprehensive and there is significant nuance across projects.

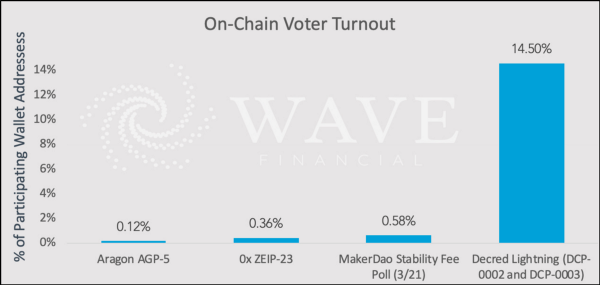

Looking a level deeper, if one were to instead measure voter participation by number of wallet addresses vs. % of circulating supply, it is clear that whales (investors with an outsized proportion of total supply) can significantly swing the numbers.

As a concrete example, looking at the number of participating wallets for Aragon’s AGP-5, voter participation decreased significantly from 9.3% represented as a % of circulating supply to 0.12% (25 addresses out of >20k). Quick plug to participate in the next Aragon vote taking place on April 25th!

That being said, the clear standouts of this analysis are the Decred Lightning Network at 86%, the Tezos Athens amendment at 72% and Cosmos’ Proposal 1 at 42% (after accounting for voter abstention).

As Cosmos launched just over 2 weeks ago on March 14th, 2019, a more fair comparison may be isolating for online voting power, which significantly improves Cosmos participation to ~73% in Proposal 1 (which officially ends on April 3rd). Additionally, after adjusting for the Tezos Foundation’s public abstention, the Athens amendment vote had a 72% participation rate as the Tezos Foundation’s baking operations manage a 30% of total “Rolls”.

It’s interesting to note that Decred, Tezos and Cosmos have consciously built on-chain governance into their identity as “self-governing” blockchains, and while these are early data points, it seems the communities are buying into the meme. In addition, all 3 protocols provide voters with a direct incentive to participate via Proof of Stake.

Decred’s ticket system allows voters to earn rewards and secure the network by locking up Decred’s native token, DCR, while coupling the ticket with on-chain voting. With over 45% of the total available supply of DCR participating in Proof of Stake mining, DCR stakeholders can earn roughly 12.5% annually by staking.

Likewise, Cosmos yields are hovering around 11% with a solid participation rate at 46.5%, which is notable given that 20% of the Genesis Supply is currently locked up (Interchain Foundation’s 10% is vesting for 6–12 months, ALL IN BITS’ 10% is subject to a 2 year vesting period).

Tezos’ similarly has a high proportion of total available supply mining via Proof of Stake at 81%, although their staking yield is slightly lower at ~7.4% annually. However, simply looking only at staking yield is only half the picture without taking into account annual inflation rates (potentially a future post).

Overall, this added financial incentive via Proof of Staking mining rewards likely contributes to Tezos’, Cosmos’ and Decred’s higher voter turnout.

Stepping back, the question naturally arises: why is there such a large delta within on-chain voting?

To start, not all proposals are created equal: without picking on 0x, ZEIP-23 may not be as important to 0x as the stability fee is for Maker to support Dai’s peg at $1). Below are general thoughts on a few high level barriers to voter participation.

Incentives

“Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome.”

— Charlie Munger

On-chain governance’s underlying assumption is that because token holders and “owners” of a protocol are one and the same, they are economically incentivized to vote in the protocol’s best interest. If tokenholders vote for a proposal that has a negative effect on the protocol, the token’s price will reflect that decision and they will lose money.

While voters are theoretically incentivized to govern given their passive ownership in the underlying network, they may need more “skin in the game” to actively participate. Otherwise voters will remain apathetic if the issue at hand is of a low degree of importance, as shown in practice.

I believe we’ll continue to see future on-chain voting implementations be strongly coupled with direct financial incentives.

Subject Matter Expertise

Tokenholders are not always subject matter experts. For example, a casual holder of MKR may not have the economics background required to vote on the implications of an increase or decrease in Maker’s stability fee. Likewise, a retail hodler likely does not have the technical expertise required to evaluate the merits of implementing ProgPOW on Ethereum. Given the time required to truly understand the ramifications of a proposal vote, voter apathy may be higher for more complex proposals.

Community leaders can help address this with market education (i.e. Jacob Arluck’s piece outlining Tezos Athens) but the average hodler just may not be willing to devote significant time researching the nuances and implications of a specific proposal.

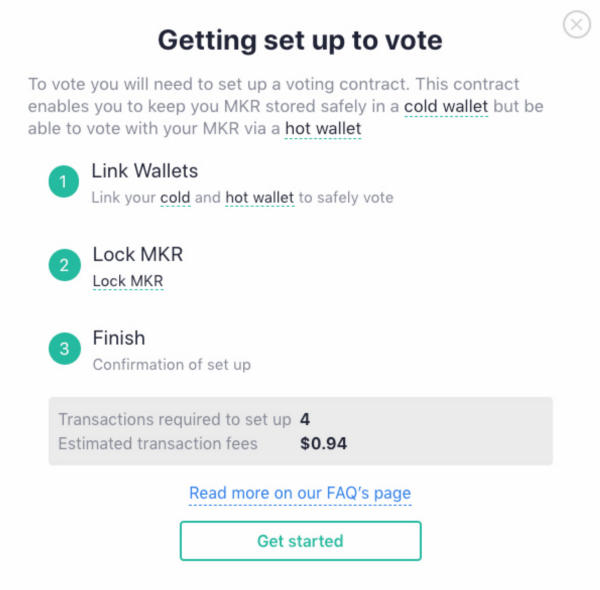

Voting Infrastructure

While there have been significant strides to improve voting infrastructure, a lack of sophisticated voting tools leads to friction when attempting to vote. Maker actually has one of the better voting user experiences, but the below snapshot showcases the reality of all voting infrastructure today and outlines the various steps required to vote on the most recent stability fee hike.

First, voters are required to have ETH in their wallets AND need to pay gas so they can connect to Maker’s voting portal, which requires 4 transactions at roughly $1. In addition, linking cold and hot wallets is a requirement — but what if smaller voters don’t have MKR on a cold wallet? Voters may get stuck and give up, as I did.

To play devil’s advocate, Maker may only want more sophisticated investors to participate and requiring a cold wallet may be a natural filter.

However, the broader point still stands that meaningful improvements are needed to reduce voter friction in order for crypto to go mainstream. This rings true not just for voting, but for decentralized applications in general.

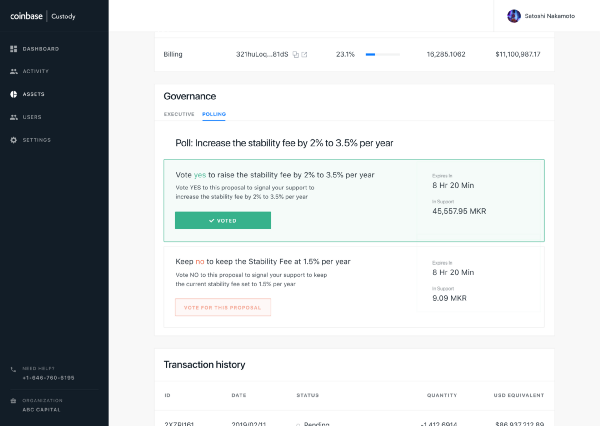

Voting infrastructure will inevitably mature, with Coinbase Custody recently announcing their addition of governance support for Maker as well as intention to add Tezos voting in Q2.

I expect other custodians will follow in Coinbase’s foot steps, which could lead to another potential point of centralization if a majority of voting takes place via 3rd party custodians.

Stakeholder Diversity

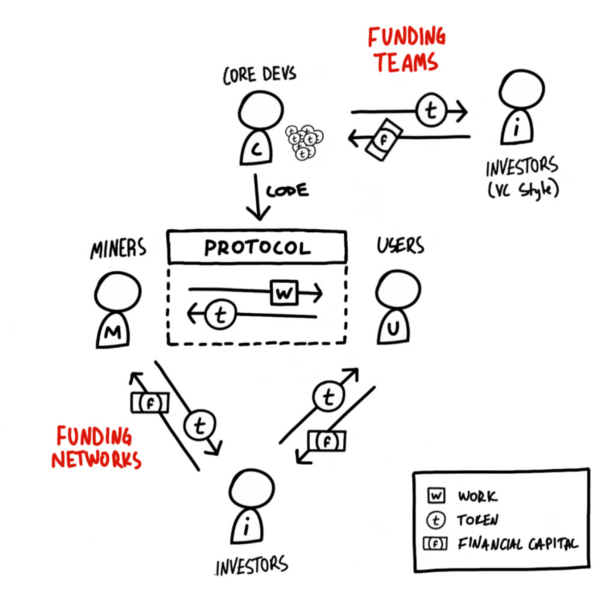

Placeholder’s Joel Monegro succinctly outlines the key stakeholders of decentralized networks in his piece, “The Cryptoeconomic Circle”: “The model describes a three-sided market between miners (the supply side), users (the demand side), and investors (the capital side). Miners opt-in to the consensus protocol and coordinate their resources to provide the network’s service in a decentralized manner, users consume the service, and investors facilitate exchange while capitalizing the network.”

Unfortunately in today’s retail-driven market with little actual utility and functionality, tokenholders are mostly investors and speculators. It’s important to have allstakeholder views represented in decentralized networks, especially users.

While the lack of stakeholder diversity is ultimately a byproduct of the ICO bubble, technological improvements will eventually lead to greater utility and a more balanced & diverse group of stakeholders.

Opportunity Costs

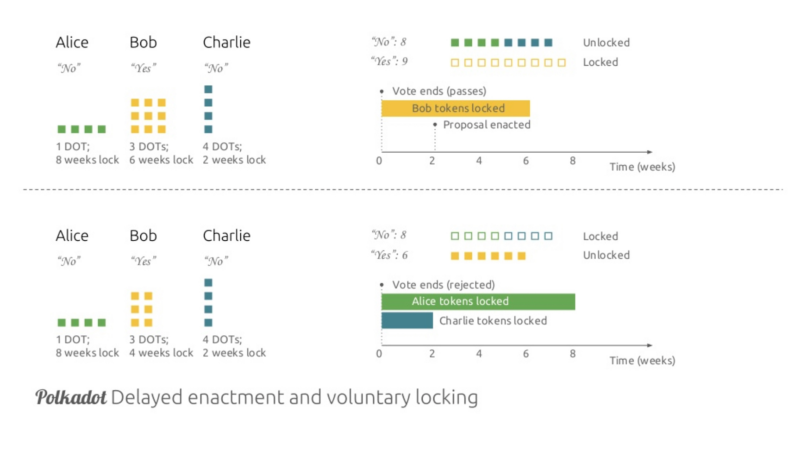

Some on-chain voting implementations require capital to be locked up for the duration of the vote (DFINITY and Polkadot both implement some form of time vote-locking, as further explored in this piece). This is by design, as voters should be held accountable for the repercussions of their vote.

While insignificant today, there are still opportunity costs when locking up tokens as the voter forgoes the ability to sell, or in the near future, earn interest from lending as #DeFi infrastructure continues to mature. Purely speculation, but if many token holders are opportunistic investors as previously hypothesized, then these speculators may value this liquidity significantly more than the future value of the protocol. Tourists vs. Citizens.

However, as we look to future on-chain governance implementations in the next section, these same opportunity costs can be leveraged to incentive behavior in unique on-chain governance designs.

Novel on-chain governance designs

It’s important to note that “one token, one vote” is merely one simple implementation of on-chain governance that has been experimented with to date. New blockchain projects are on the cusp of implementing novel on-chain governance designs, borrowing concepts like:

- Identity-based “one person, one vote”

- Delegative Democracy

- Technocracy

- Futarchy

- Weighted voting / Quadratic voting

Below are a couple exciting implementations.

Polkadot

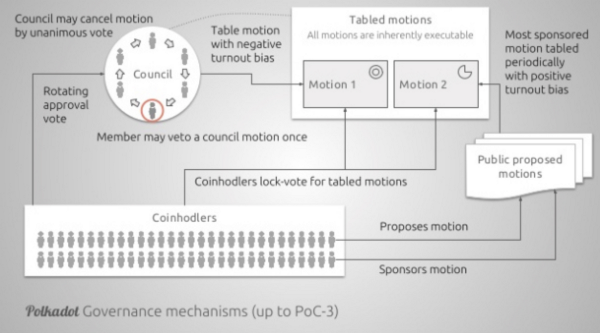

As currently outlined on GitHub, Polkadot’s governance introduces the notion of an on-chain “Council”, comprised of a fixed number of Polkadot stakeholders (envisioned to be 12-24). Each council member is elected through a staggered community Approval Vote (similar to upvoting), with members participating in a representative democracy and continuously rotating as their election term expires (1 member rotates per month).

The Polkadot Council has the power to propose new “Referenda” (specific proposals)or unanimously veto potentially malicious publicly submitted Referenda as a security backstop. The Council also directly addresses potential scenarios of low voter turnout via Adaptive Quorum Biasing.

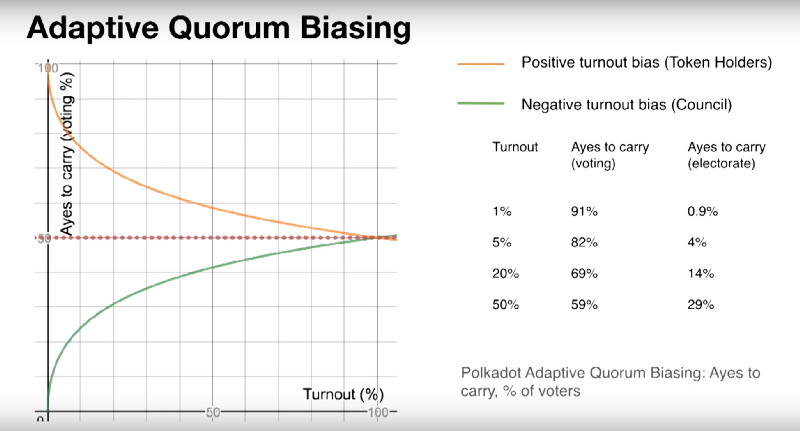

The general idea behind Adaptive Quorum Biasing is that if the Council proposes a vote, and there’s low turnout, then the proposal in question requires a lot more No votes over Yes votes to reject the Referenda in question. However, in the same low voter turnout scenario, if a regular token holder proposes a vote, the proposal needs significantly more Yes votes than No votes.

Adaptive Quorum Biasing provides Polkadot flexibility in low voter scenarios by basing voting majority requirements on turnout, making it easier or more difficult for a proposal to pass if there is no clear majority of voting power for or against it.

In addition to the introduction of a council, Polkadot leverages weighted voting, based on two variables: tokens and time.

tokens: The amount of tokens under ownership by the voter;

time: The amount of time those tokens will remain locked after the referendum has ended, measured in multiples of enactment delay and bounded between one and six.

The number of tokens are multiplied by the designated time lock to calculate the total number of votes. Weighted voting creates an interesting dynamic whereby passionate voters are able to make their votes count more by increasing their exposure to a decision.

For example, a miner may be willing to take more risk and voluntarily lock their tokens for the maximum amount of time when voting for a Referenda around a change to their bottom line. If the Referenda passes, the miner’s tokens are locked and they face the economic implications of their decision by losing the ability to sell / exit the system until their tokens are unlocked. If the Referenda does not pass, the miner’s tokens are not locked and they can sell or exit the system if they feel strongly enough.

This is an oversimplification of Polkadot governance process, so I urge the curious to read more on GitHub or watch Ryan Zurrer’s presentation at AraCon 2019.

DFINITY

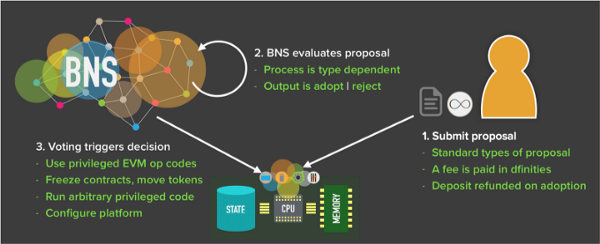

DFINITY directly addresses the shortfalls associated with the average user lacking direct subject matter expertise as previously discussed with the design of their Blockchain Nervous System (BNS), a form of Delegative Democracy:

“BNS is an intelligent system that will accept proposals from different stakeholders and then decides on these proposals using votes made by human-controlled neurons. Every, interaction with the neuron is a learning experience for the BNS and it will continuously learn and adapt to make better decisions. Note that the proposals may concern different matters such as Economics, Policy, Protocol Upgrades, Client Upgrades, Fixup or Freeze Resident etc but ultimately the system will follow a democratic voting process and decision making.”

Neuron’s within the BNS are created via a time-locked security deposit of DFINITY’s native token, DFN. The relative voting power of a Neuron is proportional to the size of total deposits. Similar to Polkadot, if a voter wants to retrieve their deposited DFN, they must “dissolve” their deposit over a significant time period (3 months or longer as outlined in initial BNS designs), creating a strong incentive for Neurons to contribute to net-positive decisions as the value of their locked DFN could fall otherwise.

In addition, DFINITY incentives voter participation by rewarding Neurons with DFN whenever they vote, with rewards being calculated proportional to the size of the Neuron security deposit and the percentage of decisions they participate in.

For example, if the BNS sets voter rewards to 1%, a Neuron that has 100 DFN deposited and participates in all decisions will return 1 DFN, while another 100 DFN sized Neuron that only participations in 50% of the decisions will only return 0.5 DFN.

While there is a clear incentive to participate in every vote, with potentially dangerous repercussions associated with blindly voting, DFINITY allows Neuron’s to follow the votes of other Neurons. By establishing Neuron follower relationships with trusted subject matter experts on relevant proposals, voters are able to delegate their decisions to perceived authorities.

For example, one can program their Neuron to follow a number of Core Developers for protocol-level proposals, or a group of Researchers they align with philosophically. This type of “liquid democracy” allows tokenholders to actively participate in on-chain votes for specific proposals they may not have the expertise to vote on.

Moving Forward

The amount of experimentation and innovation happening in this space is exciting and provides hope that the barriers associated with low voter turnout will be solved. As a majority of the novel on-chain governance designs are unproven and purely academic at this point in time, it will be fascinating to watch these implementations play out in the wild.

While on-chain governance is a double-edged sword and comes with significant trade-offs, I’m excited to continue closely watching on-chain governance evolve across the coming years. In particular, I hope to see more experimentation around Futarchy and the potential gains in efficiency speculation markets may bring to governance.

All material presented in this article represents the research analysis and opinions of the author. Nothing in this article should be construed as investment advice.